2LT Local News

Royal accolades piled on Sir John Kerr after the dismissal

Oct 31, 2020

Six weeks after his dismissal of the Whitlam Government, Kerr flew to England and visited the Queen.

He and Lady Kerr spent a weekend as guests of the Queen at her private country estate at Sandringham, and met with senior Conservative minister Lord Carrington and key members of what Charteris called “the Establishment”.

Charteris was closely involved in Kerr’s itinerary during this six-week official visit, organising his engagements with the Queen, his lunch with Carrington and Lord Blake, and his meetings with “the Establishment”.

It was all a resounding success. Charteris told Kerr that his visit had ensured that this important elite now understood his reasons for his dismissal of the Government: “your visit to London was very valuable because the Establishment here now has a much clearer idea of what happened in your constitutional crisis … most people think that what you did was right”.

Dining in London shortly before the New Year, Charteris and Kerr looked back on those tumultuous events. “Your discrimination is not limited to Constitutional issues”, Charteris observed of Kerr’s new wife, Lady Anne Kerr, in a handwritten note on Buckingham Palace letter-paper. “I bet Eugene Forsey would have liked to be a fly on the wall!”, he added.

Secret ‘Palace letters’ could illuminate Whitlam Dismissal if finally released

Soon after their return to Sydney, Lady Kerr was appointed a Commander Sister of the Order of St John, a royal order of chivalry granted at the “absolute discretion” of the Queen. The announcement was made by the Prior of the Order of St John in Australia, the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr. On the copy of the official announcement in the archives, a handwritten note reads, “Was this deliberate to counter reports that GG’s action had shocked the Royals?”

Lady Kerr’s royal honour was followed by a visit from the Queen’s second cousin and Prince Philip’s beloved uncle, Lord Louis Mountbatten, who had “much admired” Kerr’s “controversial action” in dismissing Whitlam. Mountbatten had written to Kerr immediately after the dismissal to let him know of his great admiration for him and for his “courageous and constitutionally correct” action.

In February 1976, Mountbatten stayed with Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser at Kirribilli House, visiting Kerr at Admiralty House to convey his respects and admiration in person. Kerr had no doubt that Mountbatten’s views “on the matters relating to our crisis” were shared by the Palace, telling Sir Garfield Barwick that this had been made clear to him in the Queen’s letters after the dismissal.

Charteris’s own view was clear. He could see no option but dismissal, telling Kerr that “no other course was open to you” and that he had “found no one who has been able to tell me what you ought to have done instead”. Following the Prime Minister’s formal advice to the governor-general to call the half-Senate election was, to Charteris, not a course that was open to Kerr.

The Whitlam dismissal: Four decades on

On the occasion of Kerr’s award of the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George in April 1976, Charteris wrote to congratulate him: “Many Governors-General get this award before they have had a chance to earn it in that office: no one can say that about you!”

There was no pretence at neutrality in Charteris’s comments on Whitlam’s public statements about the dismissal, in particular on Whitlam’s insistence that since supply had been passed and he had the confidence of the House, he ought to have been recommissioned as prime minister. And yet this was a firm view among those concerned by Kerr’s refusal to see the Speaker and to acknowledge the motion of the House; it was shared by legal academics Leslie Katz and Professor Colin Howard, and was hardly an outlier position.

‘Mr Whitlam could perfectly well have continued to govern and Mr Fraser should certainly have resigned’, Professor Howard wrote in a letter to The Times. Nevertheless, Charteris described his “aggravation and amazement” upon reading Whitlam’s remarks which, he told Kerr, were “to put it mildly, ‘a bit over the odds’!”

Kerr’s priority was always to protect the Queen and the monarchy. The notion of the governor-general as the Queen’s “personal representative” was, to Kerr, a literal one. In a handwritten letter to Charteris shortly before his weekend with the Queen, Kerr outlined his particular understanding of his role in relation to November 1975: “Many of the … decisions I had to make were specifically made in order to protect the Crown and the Monarchy in the future”.

Jim Cairns: Labor Left legend, Whitlam Minister and philosopher

He had not warned Whitlam, Kerr told Charteris, because he feared Whitlam might then have recalled him, and he could not “risk the outcome for the sake of the Monarchy”. With that decision made, they would all have to deal with the increasingly fractious consequences.

Although Charteris had reassured Kerr just days before the dismissal that whatever decision he made could only do the monarchy good, this had been unduly hopeful. Demonstrations and angry protests followed Kerr at every public engagement and intense debate over the dismissal continued. Kerr told Charteris, more in hope than in fact, that the demonstrators were merely “a rent a crowd” and that the furore would soon abate. It did not.

As the protests continued into 1976, the ever-needy Kerr sought royal reassurance with a feigned suggestion of resigning, not for the first time. Charteris and insistent: resignation would be seen as “an admission of error”, and in the interests of the monarchy, he should not go.

Professor Jenny Hocking is Emeritus Professor at Monash University, Distinguished Whitlam Fellow at the Whitlam Institute at Western Sydney University and award-winning biographer of Gough Whitlam. You can follow Professor Jenny Hocking on Twitter @palaceletters.

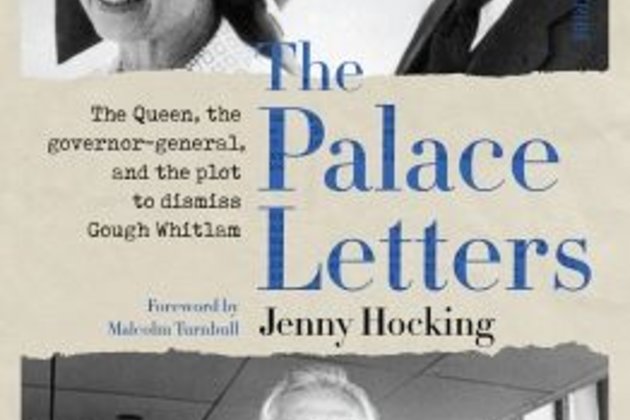

This is an edited extract from The Palace Letters: The Queen, the governor-general, and the plot to dismiss Gough Whitlam by Jenny Hocking (Scribe, $32.99), out now.